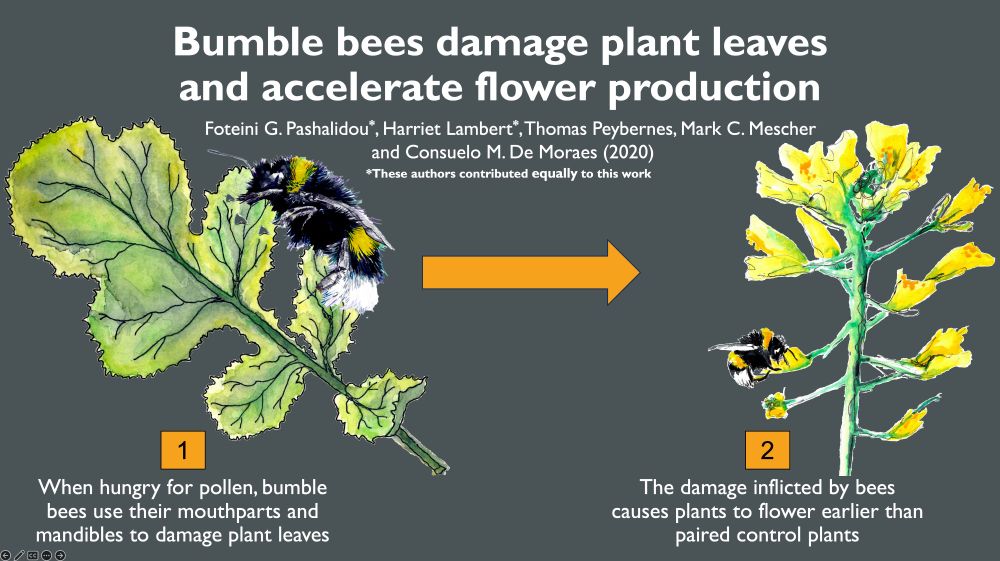

Bumble bees damage plant leaves and accelerate flower production when pollen is scarce

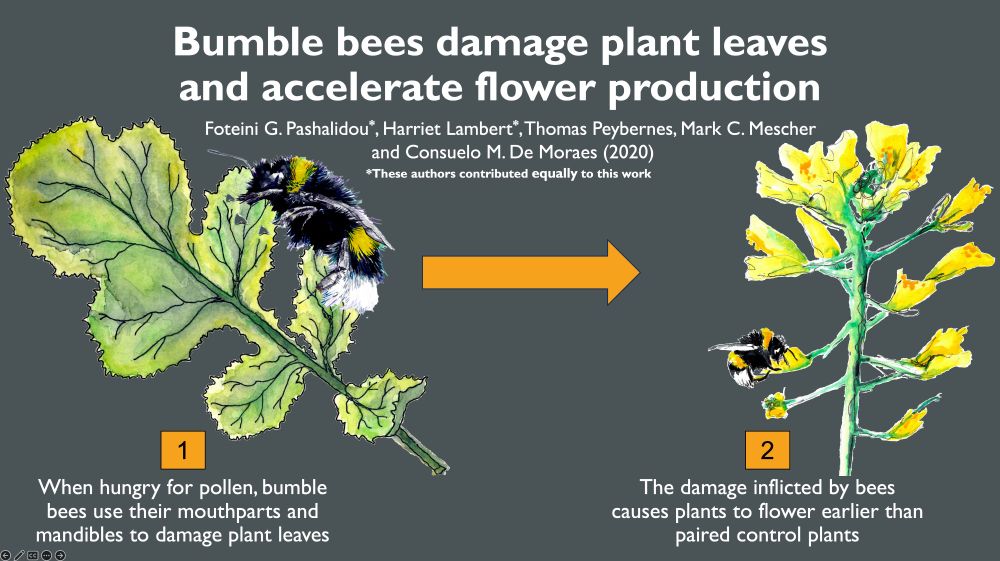

Bumble bees manipulate plants to bring about earlier flowering.

Facing a scarcity of pollen, bumblebees will nibble on the leaves of flowerless plants, causing intentional damage in a way that speeds up the production of flowers, according to a Science study from 2020.

Learn more on #WorldBeeDay: scim.ag/45hwgqy

20.05.2025 19:46 — 👍 168 🔁 38 💬 6 📌 9

yes, of course. Welcome aboard! 🐝

02.12.2024 13:54 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

Thanks for sharing! Such an interesting question—We're currently funded by an SNF Advanced Grant (data.snf.ch/grants/grant...) to explore the molecular mechanisms, adaptive significance, and ecological implications. 🐝

28.11.2024 15:10 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Thanks so much for your kind words. Stay tuned to pending updates on bumble bee behaviour and fitness! 😊

28.11.2024 13:44 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

Stay tuned for upcoming research how this impacts bumblebee performance and fitness!

28.11.2024 13:42 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

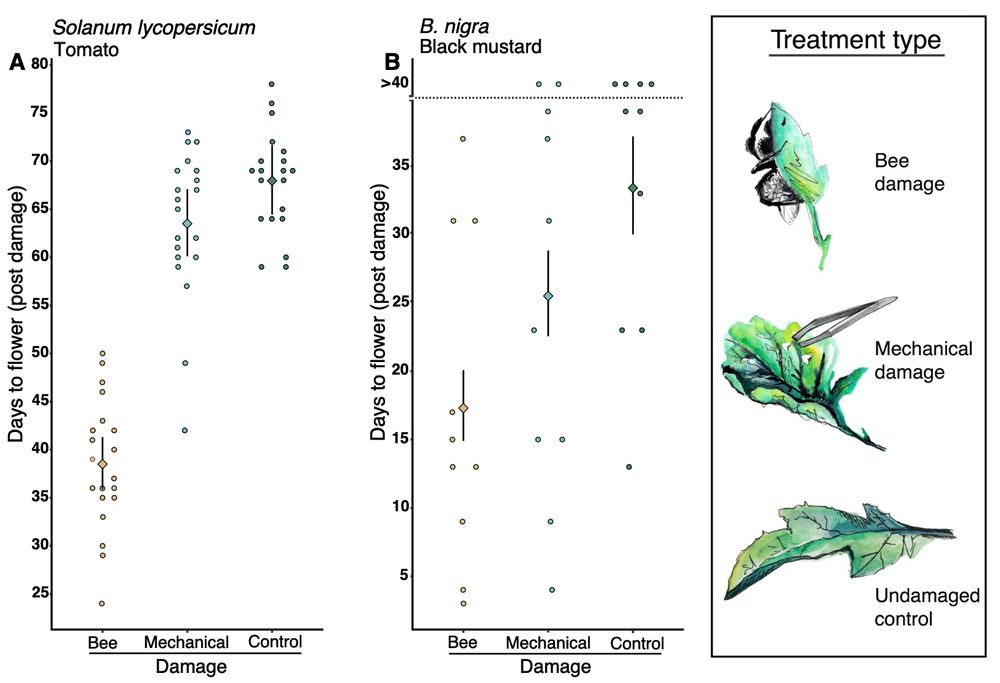

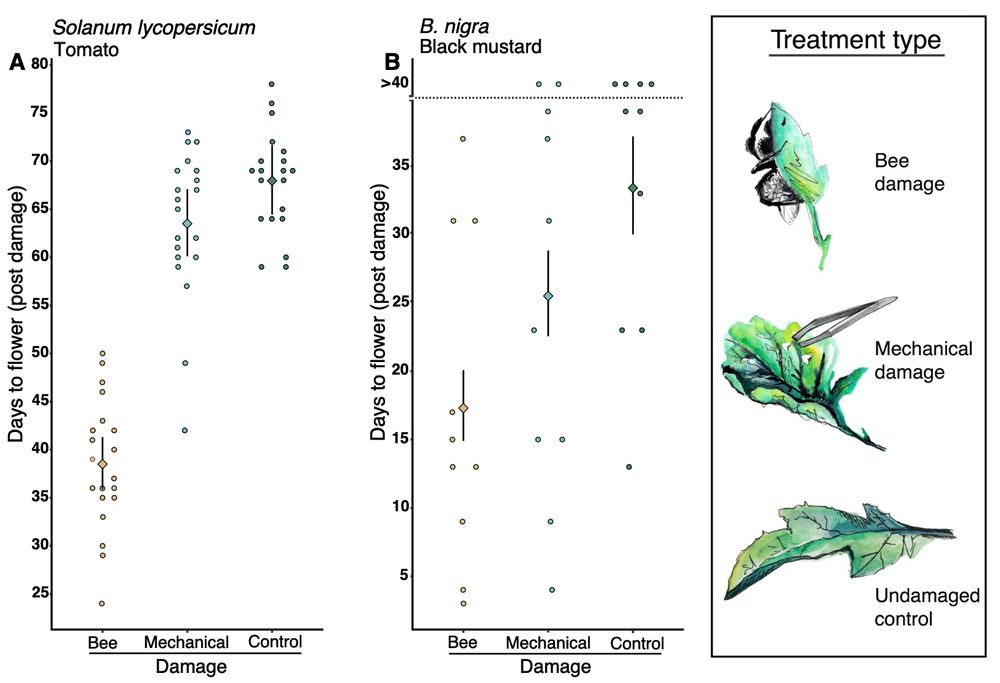

Great questions! Not all damage triggers early flowering—mechanical damage, for instance, doesn’t have the same effect. We're currently exploring the effects of leaf damage on the regulation of flowering time, as well as the proximate cues mediating plant responses to bumble bee damage.

28.11.2024 13:41 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Thank you so much for your kind words! I paint simply to relax and unwind, and bumblebees are the perfect little muses—they never stop inspiring me!

28.11.2024 13:34 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Homepage

17/17 This paper wouldn’t have been possible without my co-authors Foteini, Thomas, Mark & Consuelo and the whole #biocommunication group

@usyseth.bsky.social.

Thanks for reading & follow for updates coming soon!

Research group: biocommunication.ethz.ch

Paper link: www.science.org/doi/10.1126/...

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 17 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

The secret lives of bees as horticulturists?

Pollen-starved bumble bees may manipulate plants to fast-forward flowering

16/17 Although these findings open many more questions, particularly in regard to the adaptive nature of bee damaging, I will leave you with this; maybe bees are acting as horticulturists after all?

Thanks for the great perspective by @larschittka.bsky.social

science.sciencemag.org/content/368/...

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 24 🔁 5 💬 1 📌 1

15/17 We show that #Bumblebees engage in a remarkable behaviour to accelerate flower production when pollen is urgently needed. This strategy may also help them adapt to the challenges of environmental change.

#PhenologicalMismatch

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 14 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Waletcolour illustration of bombus pratorum worker visiting a snowdrop plant. Illustration by Harriet Lambert.

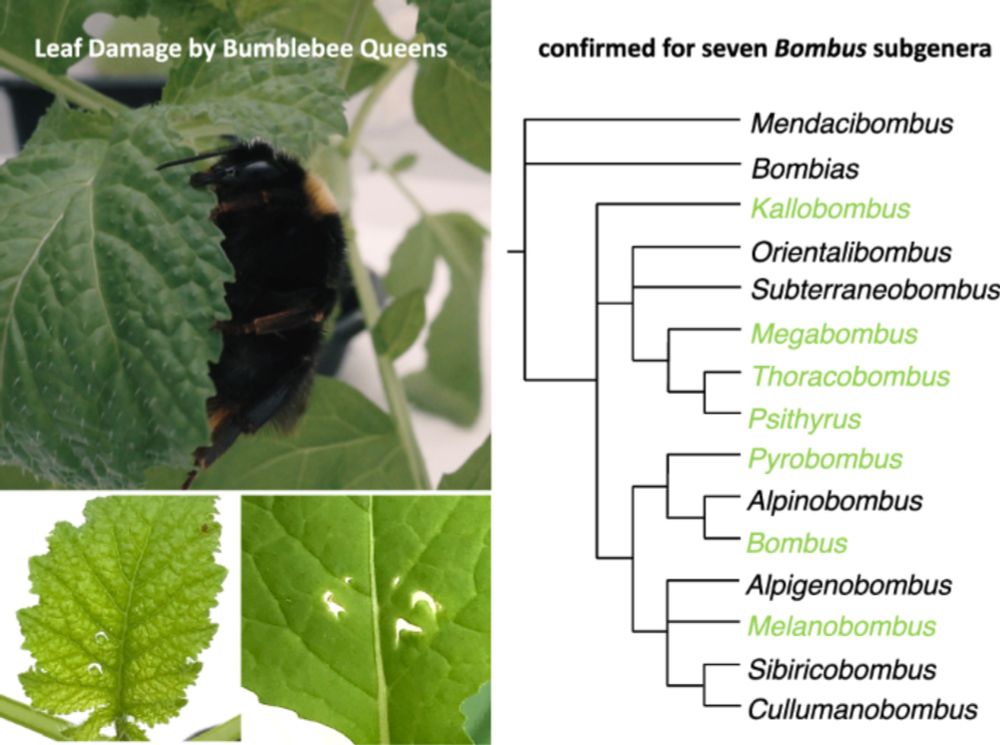

14/17 We observed wild workers from other bumble bee species damaging flowerless plant patches, demonstrating that this behaviour occurs in nature and isn’t limited to domesticated Bombus terrestris.

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 15 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

![Fig. 4 Daily measurements of damage (total number of new leaf holes) by B. terrestris workers in two outdoor experiments.

(A) 2018 experiment with queenless microcolonies. In phase 1, only flowerless plants were present locally. In phase 2, 100 plants in flower were placed adjacent to the focal patch of flowerless plants. Colors indicate individual bee colonies. Damage by bees was significantly higher in phase 1 [generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood, term = phase, df = 1, F = 712.70, P < 0.001, Akaike information criterion (AIC) 1660.9]. Dots indicate days on which weather prevented data collection. The black line represents a 7-day centered moving average of new bee holes per day. Six flowerless plant species, 36 flowerless plants per bee colony, and five bee colonies (180 flowerless plants in total). (B) 2019 experiment with queenright colonies. Colonies in both treatments were placed adjacent to focal patches of flowerless plants. Colonies in the flowering treatment also had access to 30 plants in flower, placed adjacent to the focal patch, as well as a rooftop garden planted with wildflowers. On 2 days, indicated by triangles, all colonies were given access to sugar solution for 24 hours to mitigate effects of adverse weather conditions. Damage by bees was significantly higher in the flowerless treatment (GLM fit by maximum likelihood, term = treatment, df = 1, F = 5217.7, P < 0.001, AIC 2049.3). Damage levels on roof 2 increased significantly in the month after the wildflower garden was mown (df = 30, P ≤ 0.001, AIC 2960.4, GLM). Seven flowerless plant species, 600 flowerless plants per treatment, and eight bee colonies per treatment.](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:etmgbynwifce3j4pr2awbduc/bafkreif7sgnb6l6syvcblxmt2lksonlpwgmdaol2diyzsi24pf2gl6y2oe@jpeg)

Fig. 4 Daily measurements of damage (total number of new leaf holes) by B. terrestris workers in two outdoor experiments.

(A) 2018 experiment with queenless microcolonies. In phase 1, only flowerless plants were present locally. In phase 2, 100 plants in flower were placed adjacent to the focal patch of flowerless plants. Colors indicate individual bee colonies. Damage by bees was significantly higher in phase 1 [generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood, term = phase, df = 1, F = 712.70, P < 0.001, Akaike information criterion (AIC) 1660.9]. Dots indicate days on which weather prevented data collection. The black line represents a 7-day centered moving average of new bee holes per day. Six flowerless plant species, 36 flowerless plants per bee colony, and five bee colonies (180 flowerless plants in total). (B) 2019 experiment with queenright colonies. Colonies in both treatments were placed adjacent to focal patches of flowerless plants. Colonies in the flowering treatment also had access to 30 plants in flower, placed adjacent to the focal patch, as well as a rooftop garden planted with wildflowers. On 2 days, indicated by triangles, all colonies were given access to sugar solution for 24 hours to mitigate effects of adverse weather conditions. Damage by bees was significantly higher in the flowerless treatment (GLM fit by maximum likelihood, term = treatment, df = 1, F = 5217.7, P < 0.001, AIC 2049.3). Damage levels on roof 2 increased significantly in the month after the wildflower garden was mown (df = 30, P ≤ 0.001, AIC 2960.4, GLM). Seven flowerless plant species, 600 flowerless plants per treatment, and eight bee colonies per treatment.

13/17 But how would this work outside the lab?

For two years, we repeated semi-natural experiments on roofs at @ethzurich.bsky.social. We found that bumble bee colonies always made more damage when flowers were limited.

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 14 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

![Fig. 3 Leaf damage by pollen-satiated and pollen-deprived bumble bees.

(A) Experimental setup: Two colonies were used in parallel for each trial, one of which was initially “pollen satiated” (PS) and then switched to “pollen deprived” (PD), while the other experienced the same treatments in the reverse order. Asterisks indicate days (1 and 8) when hives were weighed and new diet treatments were implemented. Adjustment (“A”) periods (days 2 to 4 and days 9 to 11) allowed colonies to acclimate to treatments. (B) Bees from pollen-deprived colonies inflicted higher levels of damage on plant leaves [F value (F) = 258, df = 32, R2 = 0.8801, P < 0.001, GLM], regardless of the order of the treatment. Additionally, the observed effects did not differ significantly among colonies (F = 258, df = 32, P = 0.732, GLM). Boxes represent the first to third quartile of the interquartile range, horizontal lines within boxes are medians, and the whiskers are the minimum and maximum values. Six hives, three replicates, and 72 plants. ***P ≤ 0.001; ns, not significant.](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:etmgbynwifce3j4pr2awbduc/bafkreiffiz2ncxqkayj4nkoeibcfv6ajjasum3pudvwemgncayv63gi6ru@jpeg)

Fig. 3 Leaf damage by pollen-satiated and pollen-deprived bumble bees.

(A) Experimental setup: Two colonies were used in parallel for each trial, one of which was initially “pollen satiated” (PS) and then switched to “pollen deprived” (PD), while the other experienced the same treatments in the reverse order. Asterisks indicate days (1 and 8) when hives were weighed and new diet treatments were implemented. Adjustment (“A”) periods (days 2 to 4 and days 9 to 11) allowed colonies to acclimate to treatments. (B) Bees from pollen-deprived colonies inflicted higher levels of damage on plant leaves [F value (F) = 258, df = 32, R2 = 0.8801, P < 0.001, GLM], regardless of the order of the treatment. Additionally, the observed effects did not differ significantly among colonies (F = 258, df = 32, P = 0.732, GLM). Boxes represent the first to third quartile of the interquartile range, horizontal lines within boxes are medians, and the whiskers are the minimum and maximum values. Six hives, three replicates, and 72 plants. ***P ≤ 0.001; ns, not significant.

12/17 We assigned colonies either a “pollen satiated” or “pollen deprived” diet. Halfway through the experiment, we switched the diets to see the effect of pollen access on damaging.

Result? Hungry bees consistently made more damage.

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 16 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

photo of microscopic pollen grains

11/17 We suspected this behaviour was related to a shortage of pollen inside the nest, the only source of protein for #bumblebees.

We started devising experiments to test whether multiple colonies would damage leaves in predictable ways.

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 11 🔁 1 💬 1 📌 0

10/17 Tomato plants came into flower a month sooner than would normally be expected 😮🐝🍅

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 24 🔁 1 💬 1 📌 0

Fig. 2 Effects of bee damage on flowering time. Flowering time of Solanum lycopersicum and Brassica nigra plants subjected to three treatments: (i) bee damage, (ii) mechanical damage, and (iii) no damage (control). Bars represent least squares means ± confidence intervals. Data were converted to a binary response variable (flowering or not flowering, for each plant on each day), and treatment effects were analyzed using generalized additive models (GAMs), avoiding assumptions of linearity. Interactions between “time since damage” and plant were modeled by smooth functions (table S1). (A) S. lycopersicum: All treatments had highly significant effects on flowering time (bee damage: P < 0.001, estimate = 13.697; mechanical damage: P < 0.001, estimate = 9.131; control: P < 0.001, estimate = −24.279). The interaction between time and plant (smooth term) was also significant: P < 0.001, estimated degrees of freedom (edf) = 0.974, Chi square (Chi.sq) = 39.49. GAM explained 77% of deviance, with coefficient of determination (R2) = 0.794 over 4800 observations. n = 20 plants per treatment. (B) B. nigra: All treatments had highly significant effects on flowering time (bee damage: P < 0.001, estimate = 2.955; mechanical damage: P < 0.001, estimate = 2.601; control: P < 0.001, estimate = −5.747). The interaction between time and plant (smooth term) was also significant: P < 0.001, edf = 0.994, Chi.sq = 181.9. GAM explained 48% of the deviance, with R2 = 0.532 over 1200 observations. n = 10 plants per treatment. On the right is a figure legend showing watercolour illustrations of the three treatments: bee damage, mechanical damage, undamaged control).

9/17 To find out, we started tracking the effect of bee damage on flower emergence.

Even with a small number of holes, plants consistently flowered earlier compared to mechanical or undamaged controls.

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 26 🔁 1 💬 1 📌 1

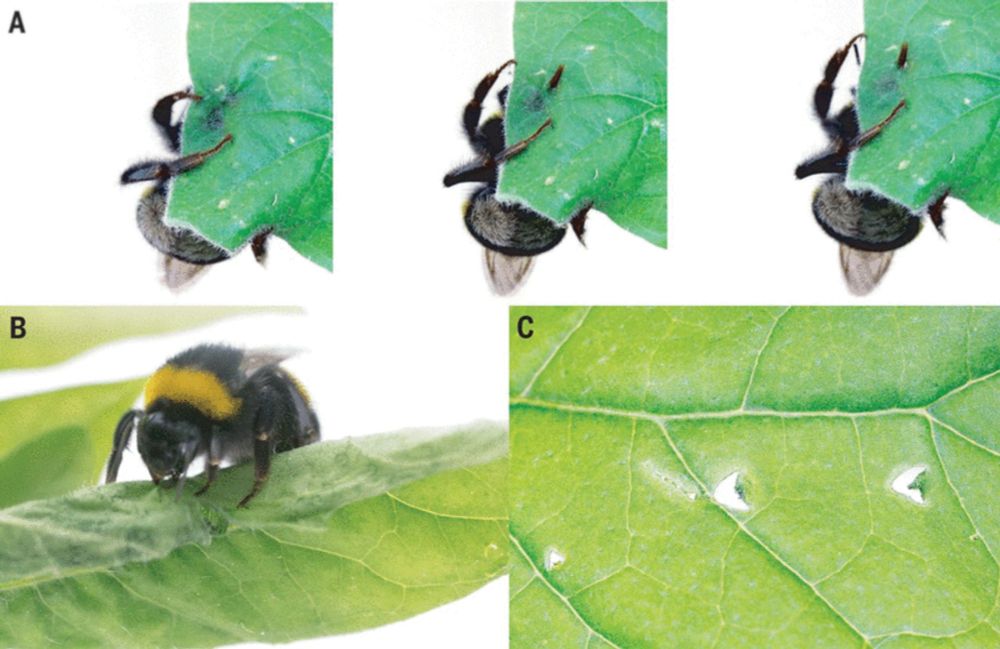

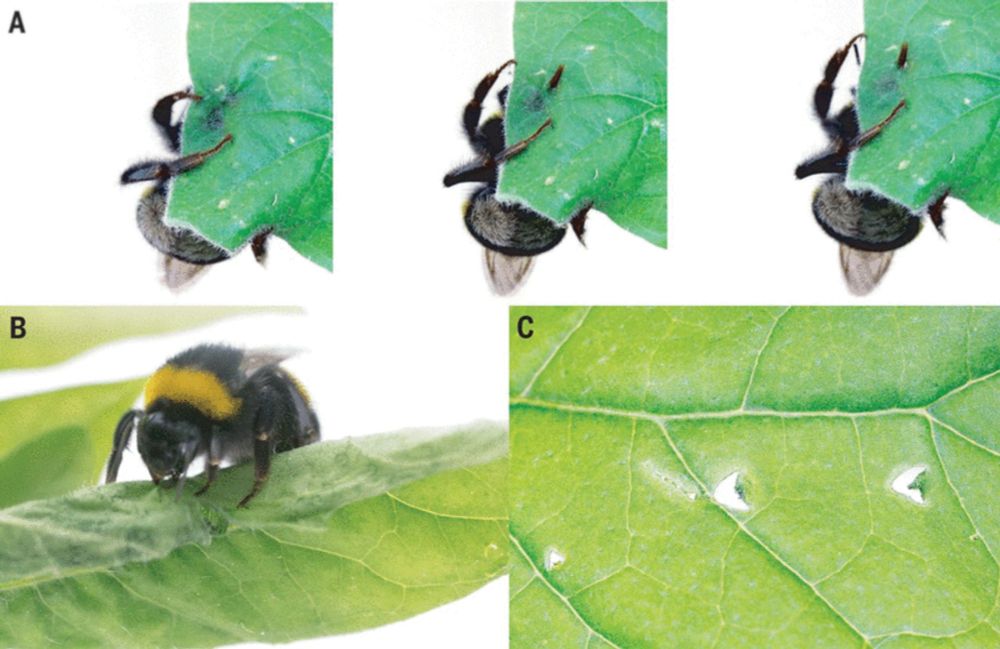

8/17 Using their mouthparts and mandibles, workers consistently made holes in multiple plant species. Each hole took a few seconds, but bees didn’t seem to be collecting tissue or getting anything from the leaf.

Why were they doing this?

Photo credit: bit.ly/hannier_pulido

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 28 🔁 2 💬 2 📌 0

Gif of a buff-tailed bumble bee worker crawling along a tomato leaf. As she crawls towards the base of the leaf, she uses her mandibles to cut a typical crescent-shaped hole in the leaf.

7/17 We noticed bumble bees behaving very strangely in the lab. Foraging workers were deliberately making holes in the leaves of flowerless plants given to them.

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 20 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

6/17 Understanding how bumble bees adapt to ongoing environmental change is more important than ever, particularly in these vulnerable early stages.

What if bumble bees could play an active role in shaping their environment? 🌏

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 18 🔁 1 💬 1 📌 0

Fig. 1 Change in community-averaged measures from the baseline (1901–1974) to the recent period (2000–2015).

Local changes in (A) thermal indices are shown. Increases indicate warmer or wetter regions and that, on average, species in a given assemblage are closer to their hot or wet limits than they have been historically. Declines indicate cooling or drying regions and that, on average, species in a given assemblage are closer to their cold or wet limits than they have been historically.

5/17 Climate change is also driving global bumble bee declines. Increasing weather events and extreme temperatures help push bees out of sync with flowers, which explains some of the dramatic losses. @tnewbold31.bsky.social

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 20 🔁 1 💬 1 📌 1

Comparison between daily nectar supply and daily demand of three common bumblebee species present on 1 km2 of farmland on: (a) Birches Farm 2016, (b) Birches Farm 2017, (c) Eastwood Farm 2017 and (d) Elmtree Farm 2017. Black lines show grams of sugar available each day on 1 km2 farmland, divided by the number of common bumblebees present on the landscape at that time that is, sugar available per individual bee (±SE). The red line shows the estimated mean daily sugar requirement of a Bombus terrestris individual at each point in the year (±SE), from Rotheray et al. (2017). Note that energy demand per individual is highest in early spring when queens are foraging and establishing colonies. Shaded regions highlight periods of nectar deficit where demand (red line) exceeds supply (black line). Note the y-axis is plotted on a log10 scale

4/17 Coordinated timing or #phenology between bumble bees and flower emergence are tightly associated.

However, scientists observe increasing ‘hunger gaps’ owing to habitat modification and loss.

@TomTimberlake92 on X

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 19 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Watercolour illustration of a buff-tailed bumble bee queen incubating her first clutch of eggs. Illustration by Harriet Lambert.

3/17 When the young queen emerges, she must rapidly establish a new nest. The failure rate of colonies is very high during early development, so having a succession of suitable flowers available is CRUCIAL.

See Bumblebees: their behaviour and ecology by

@davegoulson.bsky.social

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 25 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Watercolour illustration of a buff-tailed bumble bee queen sitting in her burrow under a layer of snow at the end of winter (illustration by Harriet Lambert)

2/17 #Bumblebees are exceptional pollinators for many fruits and vegetables.

Unlike honey bees, bumble bee colonies are seasonal. In autumn, the colony dies off, leaving only the young, mated queens to hibernate. Come spring, these queens awaken to start new nests and the cycle begins anew.

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 24 🔁 2 💬 2 📌 0

Graphical abstract of science paper 'bumble bee damage plant leaves and accelerate flower production' with a list of the authors on a grey background. On the left is a watercolour illustration of a bumble bee damaging a plant leaf with the description 'when hungry for pollen, bumble bees use their mouthparts and mandibles to damage plant leaves'. this illustration is connected by a orange arrow to a watercolour drawing of a flowering yellow black mustard plant with a bumble bee. This has the description: 2) the damage inflicted by bees causes plants to flower earlier than paired control plants.

🌟 Throwback to my 2020 research published in @science.org 🌼🐝�We showed how bumble bees actively shape their environment—making plants flower earlier to meet their needs. Nature’s engineers in action!�🧪🌏

Sharing this for anyone who missed it—let’s dive in!�[1/17] 👇

27.11.2024 10:59 — 👍 236 🔁 89 💬 8 📌 13

Homepage

17/17 This paper wouldn’t have been possible without my fantastic co-authors Foteini, Thomas, Mark & Consuelo and the whole #biocommunication group.

Thanks for reading & follow me for more!

Research group: biocommunication.ethz.ch

Paper link: science.sciencemag.org/content/368/...

26.11.2024 16:10 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

The secret lives of bees as horticulturists?

Pollen-starved bumble bees may manipulate plants to fast-forward flowering

16/17 Although these findings open many more questions, particularly in regard to the adaptive nature of bee damaging, I will leave you with this; maybe bees are acting as horticulturists after all?

Thanks for the great perspective by @larschittka.bsky.social

science.sciencemag.org/content/368/...

26.11.2024 16:10 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

photo of a bumble bee bottom poking out of a purple flower as it forces itself in to collect pollen

15/17 We show that #Bumblebees engage in a remarkable behaviour to accelerate flower production when pollen is urgently needed. This strategy may also help them adapt to the challenges of environmental change.

#PhenologicalMismatch

26.11.2024 16:10 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

watercolour illustration of a bumble bee approaching a snowdrop plant

14/17 We observed wild workers from other bumble bee species damaging flowerless plant patches, demonstrating that this behaviour occurs in nature and isn’t limited to domesticated Bombus terrestris.

26.11.2024 16:10 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

I’m campaigning for more messy spaces for nature, join our messy mission and let’s Rewild together by doing less- and letting nature do the rest!

PhD researcher - Rewilding with Beavers 🦫

Founder of the Wee Pond Project 🐸

Molecular entomology PhD student NCL @ForagingEcology 🕷️🧬 • RES Student rep 🪲 • First gen • She/They • #NeurodivergentinSTEM #PrideinEnto

Research group investigating physiology, ecology, evolutionary biology and conservation of genus Rhododendron. Sharing research, gardens, plant exploration, art, culture, events, anything and everything Rhododendron

Research scientist 🍇🖥️🌱🦠🔬

Plant Pathology | 3D+t imaging | MRI | Xrays tomography | IA | Image Analysis

Trunk diseases | Fungal Pathogens | Genetics | Molecular Biology | Grapevine | Breeding & Selection

Working at French Wine and Vine Institute

France

📍madison, wisconsin, usa 🌍conservation comms @savingcranes.bsky.social 📷photojournalist 🐦birder 📰 formerly @dallasnews.com @stltoday.com 🏳️🌈protect trans people

Bug, microbiome, and -omics enthusiast. UTSC Postdoc studying wood-eating wasps and moths. Aspiring academic twitter cool girl. 🐝🧬🪵🔬✨

Ass.-Prof. for Plant-Animal interactions @UniWien, working on the ecology and evolution of flowers, pollinators and dispersers, mostly in Melastomataceae

www.agnesdellinger.org

News, research and updates from the Department of Plant Sciences at the University of Cambridge.🌱🔬 🌾

https://www.plantsci.cam.ac.uk/

Interdisciplinary research lab, Center for Mind/Brain Sciences #CIMeC

PI: Albrecht Haase | #Neuroscience | #QuantumBiology | #Olfaction | #Vision | #Magnetoreception | #CalciumImaging | #Insects | #Honeybees | #UniTrento https://r.unitn.it/en/cimec/nphys

Entomologist and artist. All views are my own.

Alberta, Canada.

They/them

🍉🌈🏳️⚧️

Plants little forests, pocket forests and pocket meadows as songs, poems, love letters to the land. Adjunct @QueensU

🌱 #History, #Botany, #Plants, #Gardening, #Art, #Allotment, Economic & Social History, Small-scale food production, Cricket. Mending old things and restoring old houses. Location 🇬🇧

I reply to comments on my posts, but not often to DMs

PhD student in Jacob Koella's lab at Neuchâtel | Evolutionary biologist interested in how host-parasite interactions evolve and influence each other | he/him |

📍Neuchâtel, Switzerland

Welsh postdoc @ The Crick with Dr. Eachan Johnson.

TB and ESKAPE pathogen research. Interested in high-throughput, genomics, and chem biol.

PhD from University of Birmingham with Prof. Jess Blair.

Views my own. (she/her)

Microbiologist / Scientific Photographer / Visionary / Artist / Researcher

Discover the beauty of fungal endophytes with me! 🍄✨️

www.fungalgalaxies.com

Limited edition prints for sale.

Copyright: Diego Dylan Bianchi 🇮🇹

PhD - Trinity College Dublin 🇮🇪

Librarian, entomologist, New Zealand

🇮🇹🇳🇿🇦🇺 |Molecular Entomologist |

Biodiversity explorer | ❤️psyllids❤️ |

Metabarcoding & Biosecurity |

PhD student at UCF studying Ichneumonoidea comparative genomics. Masters is in Ophioninae systematics from UCSB. sometimes I make an art or say a funny

Conservation biologist with focus on botanics and entomology. I love macrophotography of all fauna & flora but especially of insects and spiders. Pics & opinions are my own.

Currently in Cape Town. She/her

https://www.inaturalist.org/people/elliklaus

Professor, University of Bergen UiB SVT Centre for the study of the Sciences and the Humanities. #post-normal_science #sustainability #actionable_knowledge #uncertainty #precautionary_principle #climate_change_adaptation #insect_decline #pollinator_decline

![Fig. 4 Daily measurements of damage (total number of new leaf holes) by B. terrestris workers in two outdoor experiments.

(A) 2018 experiment with queenless microcolonies. In phase 1, only flowerless plants were present locally. In phase 2, 100 plants in flower were placed adjacent to the focal patch of flowerless plants. Colors indicate individual bee colonies. Damage by bees was significantly higher in phase 1 [generalized linear mixed model fit by maximum likelihood, term = phase, df = 1, F = 712.70, P < 0.001, Akaike information criterion (AIC) 1660.9]. Dots indicate days on which weather prevented data collection. The black line represents a 7-day centered moving average of new bee holes per day. Six flowerless plant species, 36 flowerless plants per bee colony, and five bee colonies (180 flowerless plants in total). (B) 2019 experiment with queenright colonies. Colonies in both treatments were placed adjacent to focal patches of flowerless plants. Colonies in the flowering treatment also had access to 30 plants in flower, placed adjacent to the focal patch, as well as a rooftop garden planted with wildflowers. On 2 days, indicated by triangles, all colonies were given access to sugar solution for 24 hours to mitigate effects of adverse weather conditions. Damage by bees was significantly higher in the flowerless treatment (GLM fit by maximum likelihood, term = treatment, df = 1, F = 5217.7, P < 0.001, AIC 2049.3). Damage levels on roof 2 increased significantly in the month after the wildflower garden was mown (df = 30, P ≤ 0.001, AIC 2960.4, GLM). Seven flowerless plant species, 600 flowerless plants per treatment, and eight bee colonies per treatment.](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:etmgbynwifce3j4pr2awbduc/bafkreif7sgnb6l6syvcblxmt2lksonlpwgmdaol2diyzsi24pf2gl6y2oe@jpeg)

![Fig. 3 Leaf damage by pollen-satiated and pollen-deprived bumble bees.

(A) Experimental setup: Two colonies were used in parallel for each trial, one of which was initially “pollen satiated” (PS) and then switched to “pollen deprived” (PD), while the other experienced the same treatments in the reverse order. Asterisks indicate days (1 and 8) when hives were weighed and new diet treatments were implemented. Adjustment (“A”) periods (days 2 to 4 and days 9 to 11) allowed colonies to acclimate to treatments. (B) Bees from pollen-deprived colonies inflicted higher levels of damage on plant leaves [F value (F) = 258, df = 32, R2 = 0.8801, P < 0.001, GLM], regardless of the order of the treatment. Additionally, the observed effects did not differ significantly among colonies (F = 258, df = 32, P = 0.732, GLM). Boxes represent the first to third quartile of the interquartile range, horizontal lines within boxes are medians, and the whiskers are the minimum and maximum values. Six hives, three replicates, and 72 plants. ***P ≤ 0.001; ns, not significant.](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:etmgbynwifce3j4pr2awbduc/bafkreiffiz2ncxqkayj4nkoeibcfv6ajjasum3pudvwemgncayv63gi6ru@jpeg)