This is one of the most important, and least understood, details in the value of higher education - it's benefits are reaped very differently by rich and poor students.

20.07.2025 23:01 — 👍 8 🔁 2 💬 0 📌 0@zbleemer.bsky.social

Assistant Professor of Economics at Princeton and NBER | Education and Economic Mobility

This is one of the most important, and least understood, details in the value of higher education - it's benefits are reaped very differently by rich and poor students.

20.07.2025 23:01 — 👍 8 🔁 2 💬 0 📌 0

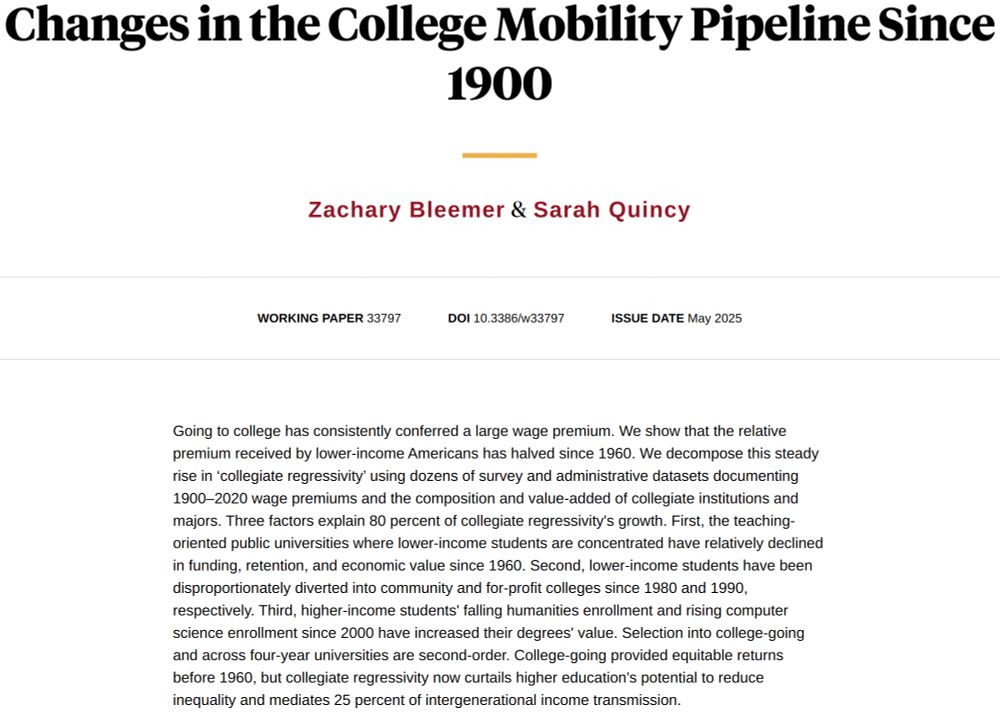

This depressing new NBER working paper finds that while the returns to a college education are still clearly positive for everyone, the benefits for students from lower-income families have declined over time due to fewer resources going to regional institutions.

19.05.2025 09:28 — 👍 120 🔁 44 💬 1 📌 4Interesting! You're right to point out that history is the highest-wage HUM majors, but we do put it in that category.

Most of our surveys only report one major; when they have two, we just take the first. We could randomize instead; I wonder if your EDU students would list history first or second!

Important paper by Bleemer and Quincy: Since 1960, the college wage premium has become less equal. Lower-income students now get far less out of college than their higher-income peers.

www.nber.org/papers/w33797

If you have questions about, e.g.:

1. Things it's not: selection into college/the Ivy League/selectivity and the SAT/rising tuition;

2. Causal interpretability;

3. What about women;

4. Details on data construction;

or more, you should definitely take a look at the full study!

Thanks for reading! You can find an ungated version of the study here:

zacharybleemer.com/wp-content/u...

If lower-income kids still got the same relative value from going to college as in 1960 – even holding fixed *who* goes to college – then intergenerational income transmission in the US would fall ~25%.

This explains most of the decline in economic mobility since the '60s.

Altogether, changes in institutional returns (30%), major composition (25%), and two-year and for-profit composition (20%) explain most of the regressivity trend.

This is why going to college has become less valuable for poor students.

The for-profit sector peaked in the 2000s and has dramatically shrunk. But recent growth of the community colleges disproportionately holds poor students back.

Poor students' diversion to these lower-value colleges explains about 20% of the rise in collegiate regressivity.

Trend 3️⃣ explaining the rise of collegiate regressivity is the growth of community colleges and the for-profit sector.

Students who attend these schools derive lower value-added from them. Since the 1980s, those students have been disproportionately poor.

Today, 10% of male college graduates earn CS degrees. It's doubled in 10 years.

Most of that growth was driven by rich students, making college more regressive.

Why? As I've shown before, universities exclude poor students from CS using restrictions: x.com/zbleemer/sta...

We all know that the humanities are shrinking. It turns out that most of that decline is coming from rich students.

Possibly for the first time ever, poor students are now more likely to be humanities majors than rich students.

That's bad for economic mobility.

Sometimes, like in the 1920s or the 1990s, poor and rich college students earn similar-value majors.

Today, though, poor students earn much lower-paying majors than the rich. This explains 25% of regressivity.

Two disciplines are most at fault: humanities and computer science.

Trend 2️⃣ driving collegiate regressivity is the most surprising. This one is about college majors.

There are huge differences in wage value across majors. They haven't changed much over time.

Humanities at the bottom. Engineering at the top. The gap has widened.

If colleges' value-added hadn't changed since 1960, rich and poor students would have always attended similar-value schools.

But using current value-added, poor students attend lower-value uni's.

Teaching-oriented publics' deterioration explains 30% of collegiate regressivity.

College quality varies widely: e.g. research-oriented publics have 2x the per-student revenue of teaching-oriented publics.

That money buys value. We measure colleges' "value-added": the degree to which they increase future wages.

Poor students' colleges' value has fallen.

Number 1️⃣ is about changes in colleges' quality.

Rich students have always mostly attended private and research public universities. Poor students mostly go to teaching-oriented publics.

That's still true. But the teaching-oriented publics have deteriorated in value.

We first plot the slope of the college-going premium by parental income over time. Positive numbers mean the premium is regressive.

Between 1920 and 1960, the premium was equal for the rich and poor. It's been getting more regressive since then.

Three factors explain the trend:

To identify and trace the causes of rising collegiate regressivity, we combine dozens of nationally-representative survey and admin datasets spanning 1900-2023.

The data include the parental income, college, major, and early-30s wages of hundreds of thousands of Americans.

In the early 1900s, the wage premium for going to college was the same for sons from both rich and poor families : +10 ranks (+15%) in the wage distribution.

Today, the wage premium has grown for the rich but sharply fallen for the poor. We call this "collegiate regressivity".

New study: The relative wage premium for going to college has halved for low-income Americans since 1960.

What is to blame? Rising selectivity? Tuition hikes? State disinvestment? We decompose changes in the premium since 1900 to find out.

🧵#EconTwitter nber.org/papers/w33797

Why are wages in Paris or NYC higher than in other cities?

In a new WP with @paulinecarry.bsky.social & @bennykleinman.bsky.social, we decompose spatial disparities btw “location effects” and the local composition of workers and establishments.

New data on firm mobility + double-mover design.

🧵⬇️

We are hiring an education researcher to join the @capolicylab.bsky.social and @berkeleycshe.bsky.social teams. You'll work on projects using administrative data relating to California higher education. Here's more information: capolicylab.org/careers/rese...

09.04.2025 15:54 — 👍 20 🔁 26 💬 1 📌 0

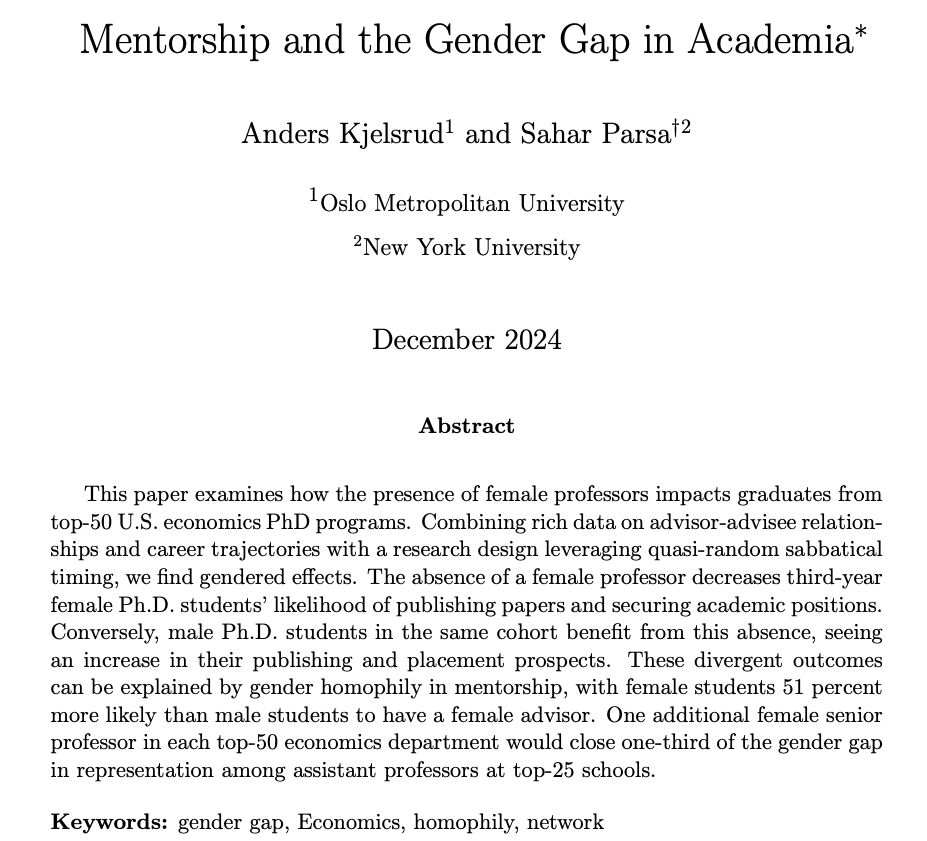

**New working paper**

How does the under-representation of females in Economics affect the career trajectory of female Ph.D. students?

Sahar Parsa and I look at this in a new working paper by exploring sabbatical leaves taken by female professors at top-50 US Econ departments.

I will discuss recent trends in meritocracy, access, and the allocation of US higher education on a livestreamed ASSA panel tomorrow (Sunday) at 8 am PST, 11 EST.

Livestream here: www.aeaweb.org/conference/l...

Black and Hispanic college graduates have been steadily earning degrees in relatively lower-paying majors since 2000. The main reason is new GPA-based restrictions on major choice, from Zachary Bleemer and Aashish Mehta https://www.nber.org/papers/w33269

24.12.2024 16:00 — 👍 44 🔁 14 💬 1 📌 0

College Major Restrictions and Student Stratification Zachary Bleemer & Aashish Mehta X LinkedIn Email Working Paper 33269 DOI 10.3386/w33269 Issue Date December 2024 Underrepresented minority (URM) college students have been steadily earning degrees in relatively less lucrative fields of study since the mid-1990s. A decomposition reveals that this widening gap is principally explained by rising stratification at public research universities, many of which increasingly prevent students with poor introductory grades from declaring popular majors. We investigate these major restriction policies by constructing a novel 50-year dataset covering four public research universities' student transcripts and employing a staggered difference-in-difference design around the implementation of 25 GPA-based restrictions. Restrictions disproportionately filter out less-prepared students with fewer pre-college academic opportunities, decreasing average URM enrollment shares by 20 percent. They do not measurably improve allocative efficiency across majors, departments' wage value-added, or filtered students' educational attainment. Using first-term course enrollments to identify students who intend to earn restricted majors, we find that major restrictions disproportionately lead URM students toward less lucrative majors, explaining nearly all growth in within-institution ethnic stratification since the 1990s.

TLDR: A new and IMPORTANT study finds that GPA cutoffs for high paying majors (like engineering and business) not only fail to improve student outcomes, but have also disproportionately driven minorities away from high-paying fields since the 1990s.

BRUH. #econsky #blacksky #science

Project Talent! They were born 1941-1946 and the same size is over 400,000. You get a wage measure at age 29. It's pretty easy to get the data; free agreement with AIR.

13.12.2024 19:21 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Calling young applied microeconomists: come hang out at Princeton for a few days in March for a great conference! Papers due Dec. 22.

irs.princeton.edu/news/2024/nl...

#Econtwitter

Jess's paper has much more than that! Take a look for yourself:

www.jessica-min.com

And while you're at it, consider giving her a job! She's a fantastic labor/public economist with lots more in the pipeline.