Speaker list for the Autumn 2025 Cooperation Colloquia:

2025-09-12 | Doruk İriş (Sogang University)

2025-09-26 | Talbot M. Andrews (Cornell University)

2025-10-10 | Setayesh Radkani (MIT)

2025-10-24 | Christian Ruff (University of Zürich)

2025-11-07 | Bianca Beersma (Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam)

2025-11-21 | Kristopher M. Smith (Washington State University)

2025-12-05 | Alex Mesoudi (University of Exeter)

⚡ Autumn 2025 Cooperation Colloquia ⚡

We are excited to announce the next run of Cooperation Colloquia. With @talbotmandrews.bsky.social, @setayeshradkani.bsky.social, @kris-smith.bsky.social, @alexmesoudi.com, & more.

Every second Friday, 15:00 CE(S)T

Sign up here: list.ku.dk/postorius/li...

26.08.2025 10:31 — 👍 8 🔁 8 💬 0 📌 1

Everyday Revenge

We are interested in stories of everyday revenge—cases where you successfully got back at someone after being wronged. Please think up an experience of when you took revenge and tell us about it.

Pl...

@anagantman.bsky.social @jowylie.bsky.social and I are starting to study everyday revenge. Have you ever successfully gotten back at someone after being wronged? We would love to hear about it.

docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1F...

#PsychSciSky #socialpsyc #cognition

08.08.2025 14:46 — 👍 28 🔁 19 💬 1 📌 1

Also sharing a beautiful illustration of these ideas by my lovely and talented 👩🎨 friend, Adhara Martellini!

08.08.2025 14:57 — 👍 6 🔁 1 💬 0 📌 0

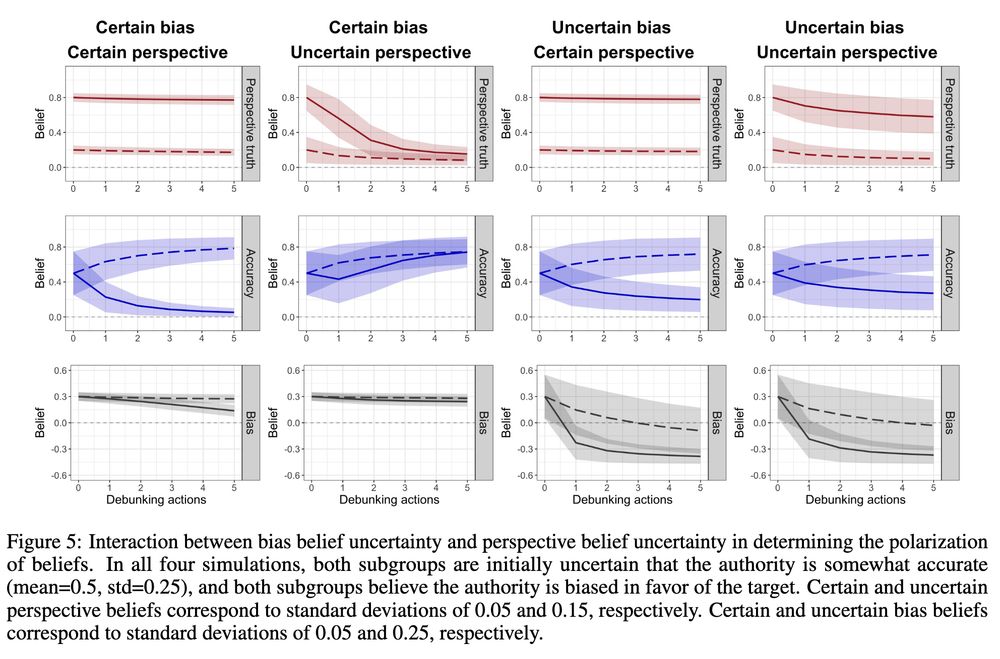

Bottom line: The same punishment can teach different lessons to different people depending on their prior beliefs, even when everyone is reasoning rationally. So, even well-meant punishment can widen divides or fuel polarization.

10/10

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

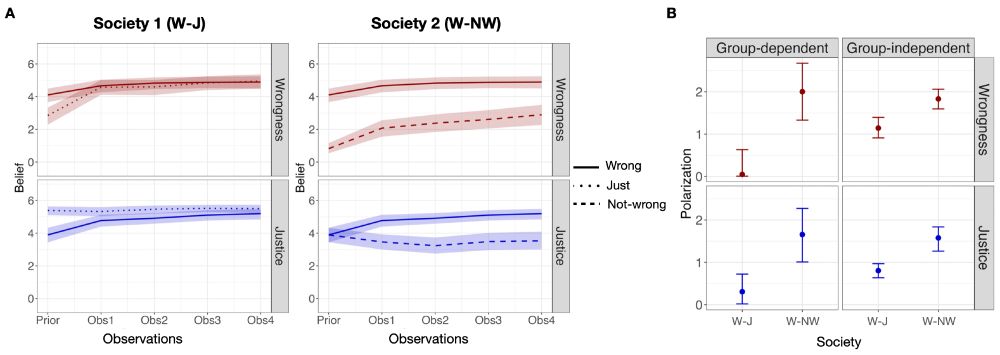

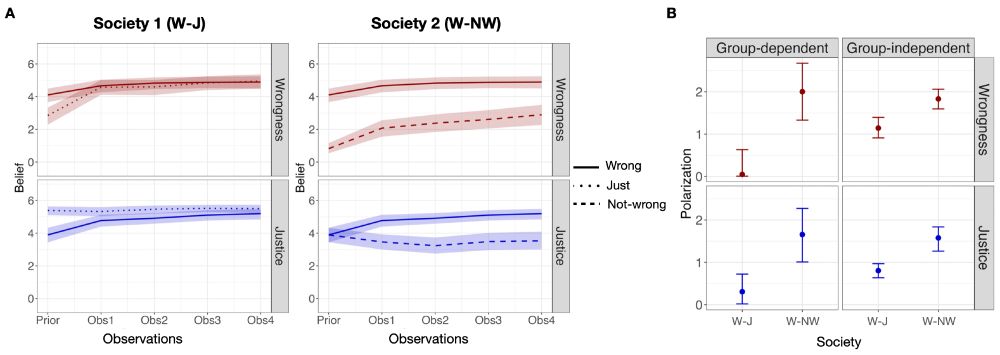

Finding 4️⃣: In a separate study, we found that repeated punishments can fail to close societal divides, and may even polarize initially shared beliefs. Our model predicts when punishment works in reducing polarization and when it backfires!

9/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

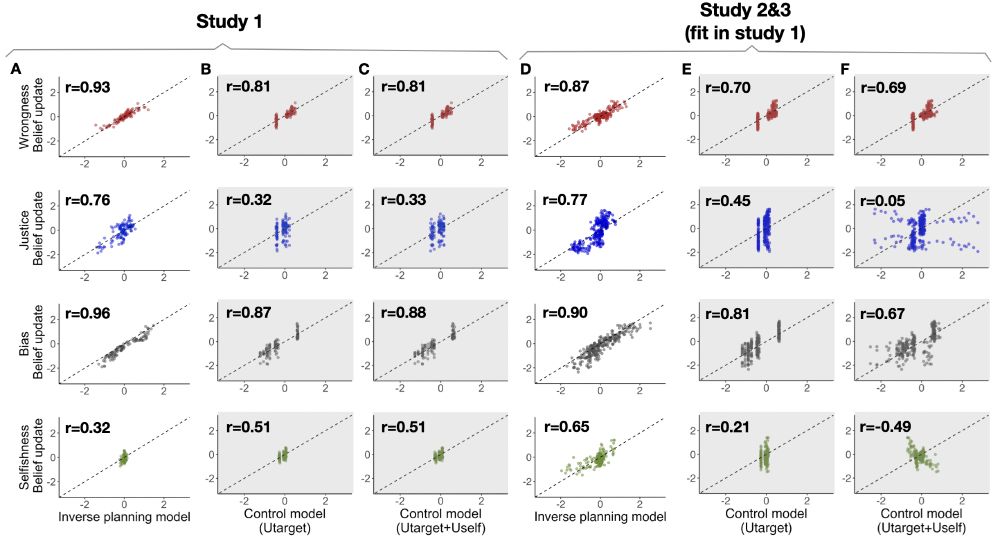

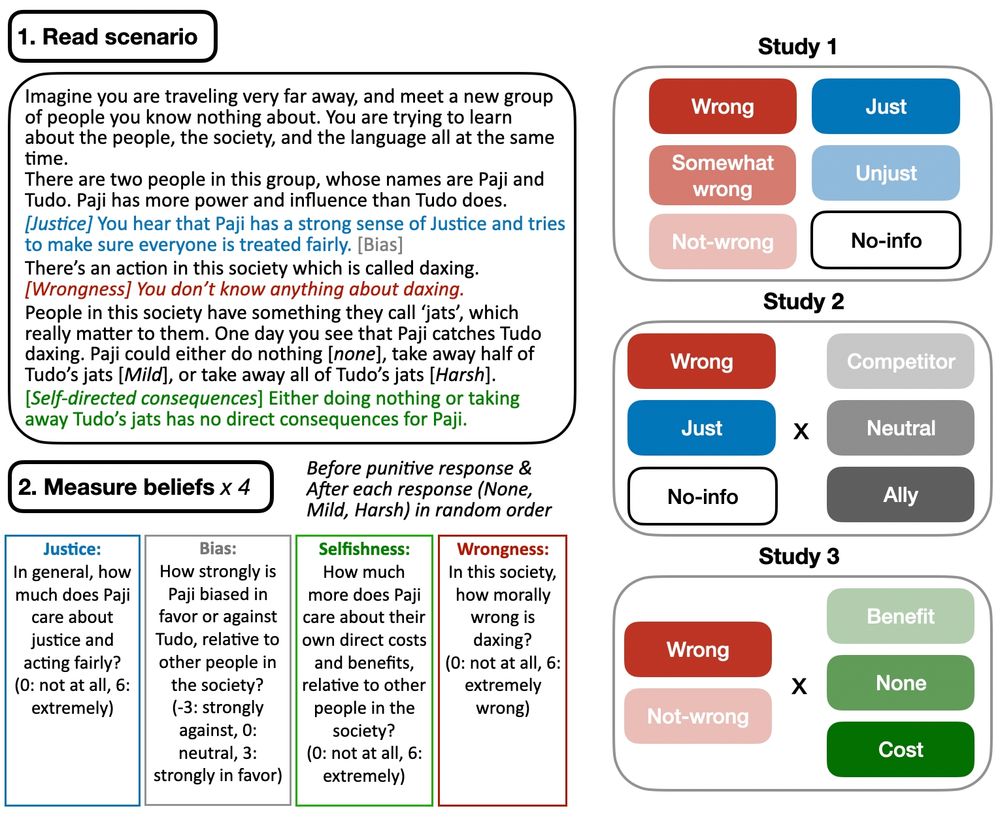

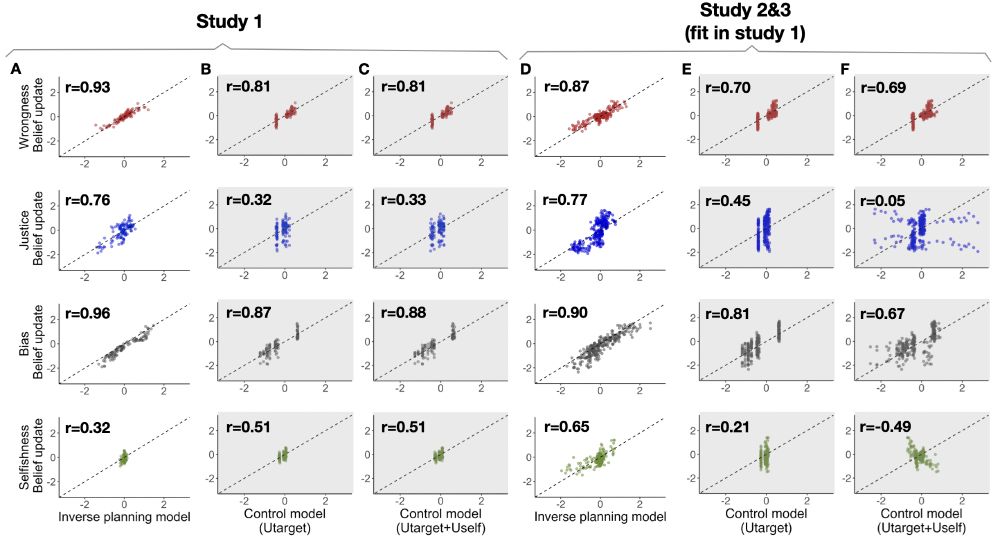

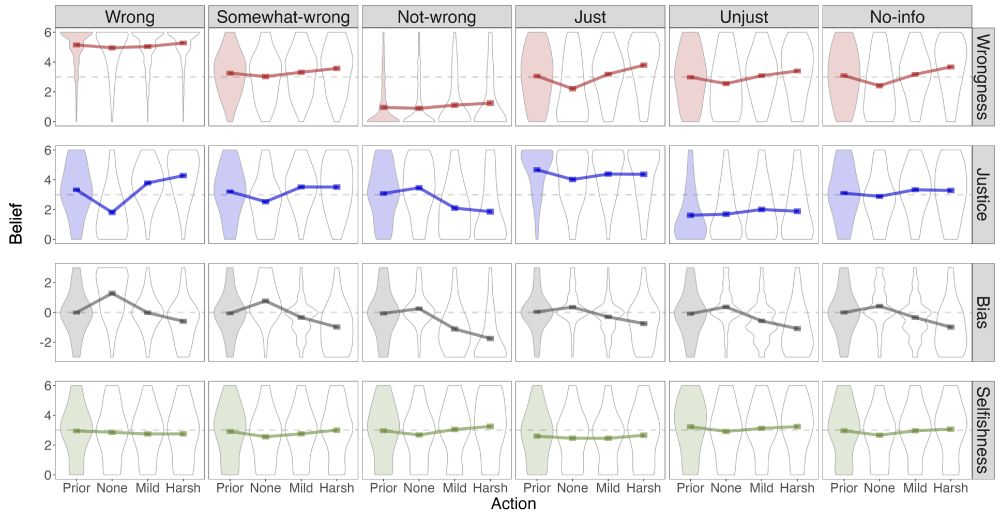

Finding 3️⃣: Our computational model simultaneously captures people’s belief updates about the act and the authority, even in novel prior conditions that the model has never seen before 👀; even better than control models that are fit to predict each belief separately!

8/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

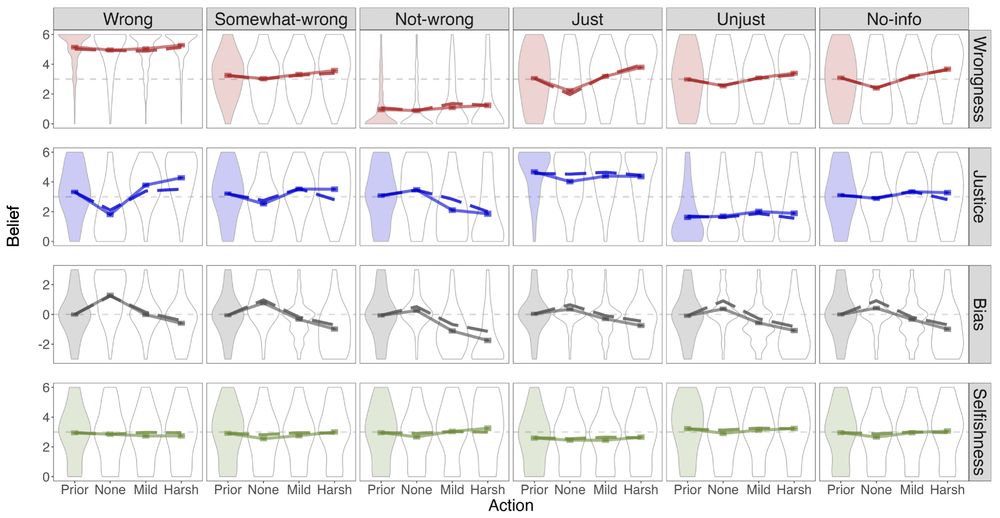

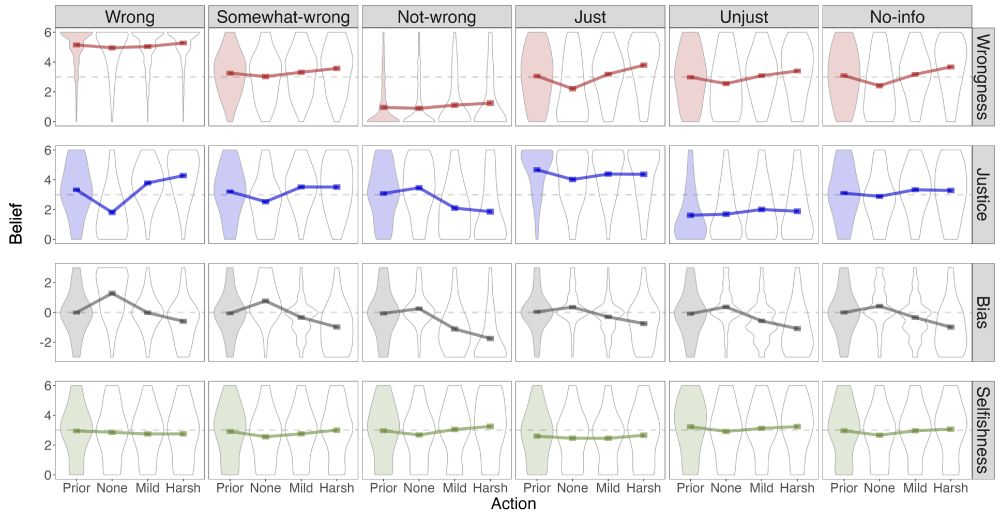

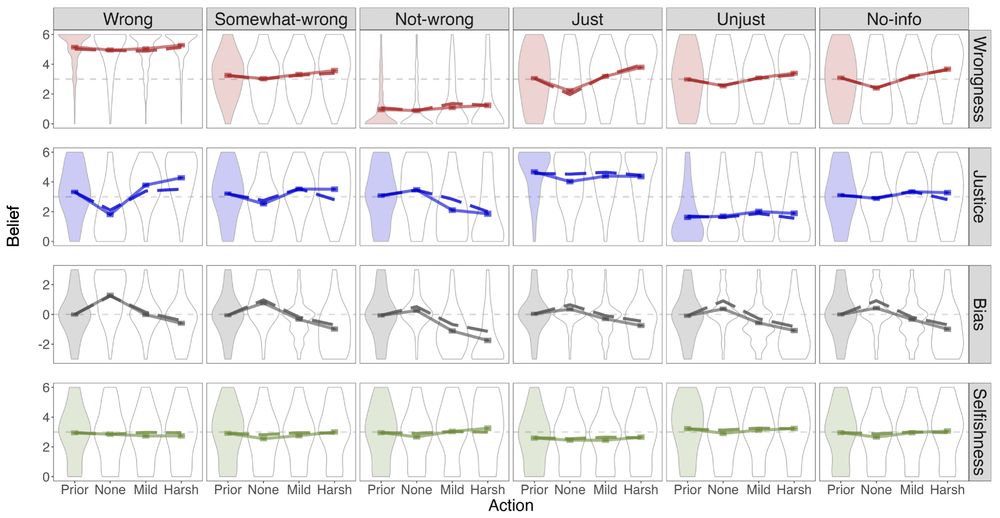

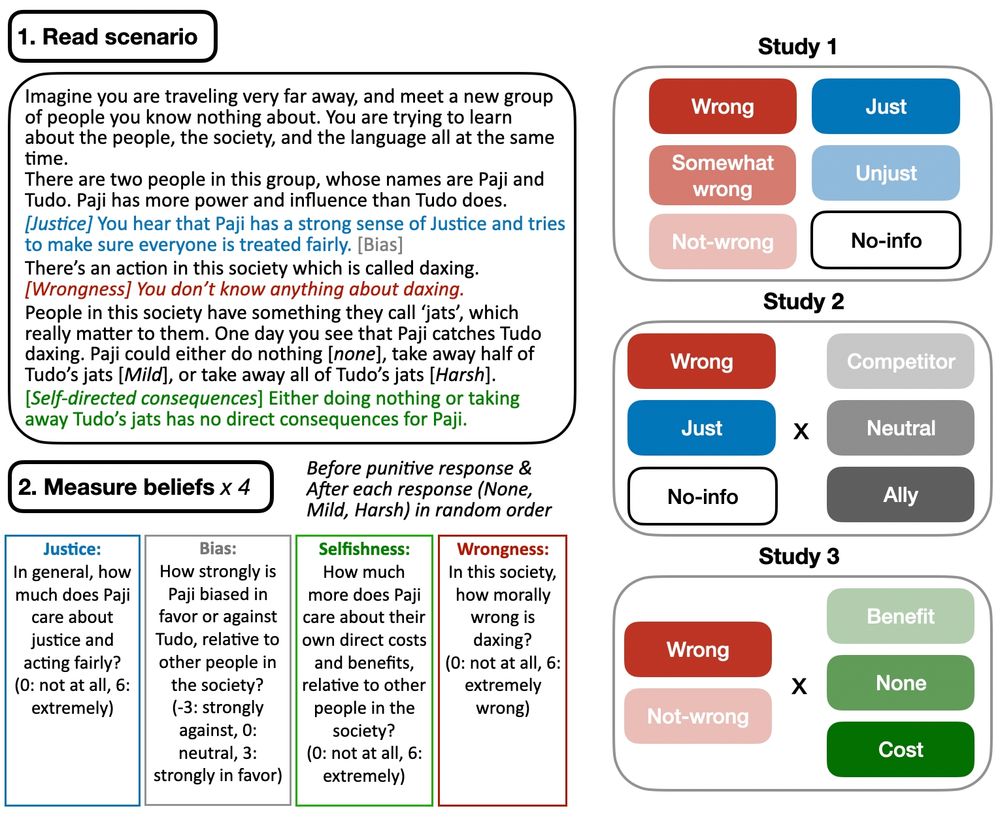

Finding 2️⃣: People’s prior beliefs shape their reasoning about punishment. The same punishment can lead to contrasting inferences, depending on the value and uncertainty of prior beliefs about both the act and the authority.

7/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

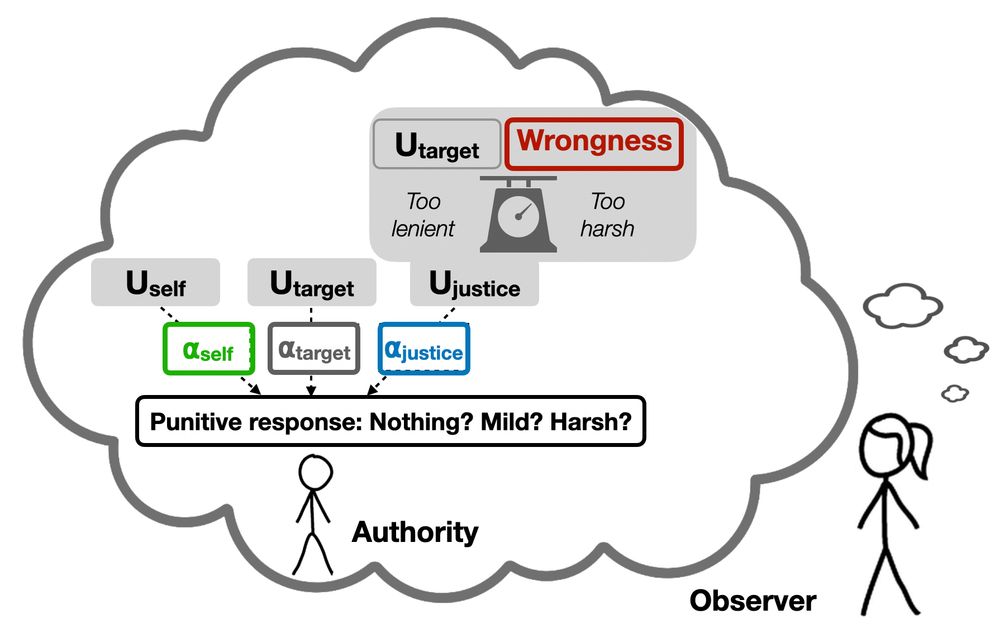

Finding 1️⃣: From observing punishment (or no punishment!), people simultaneously update their beliefs about the wrongness of the target act, and about the authority’s motivations and values.

6/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Across 3 studies, we used imaginary villages to experimentally control people’s pre-existing beliefs about the target act and the authority. We then measured how observing punishment with different severities moves their beliefs.

5/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 3 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

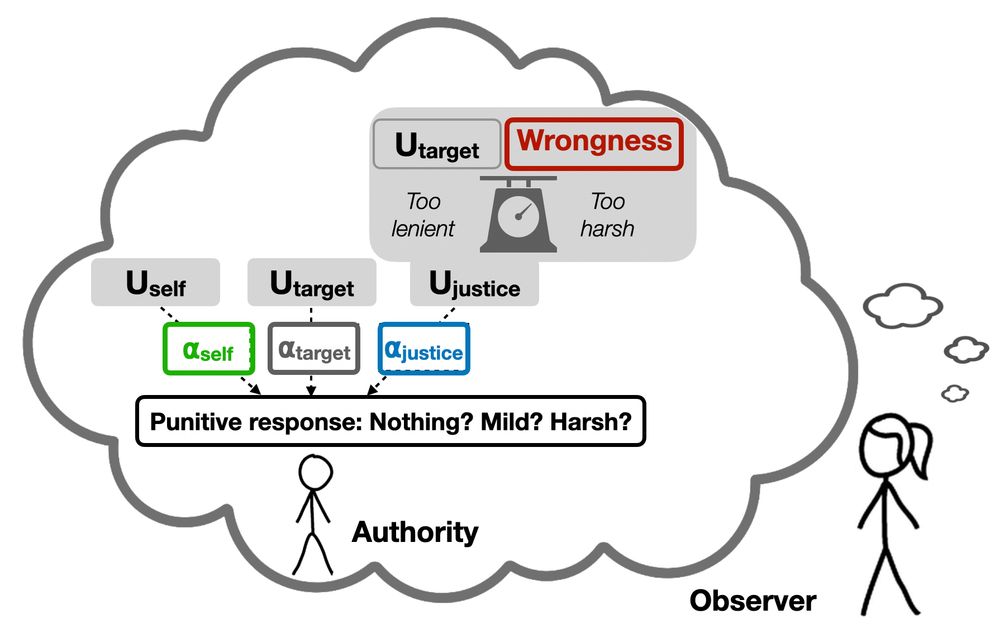

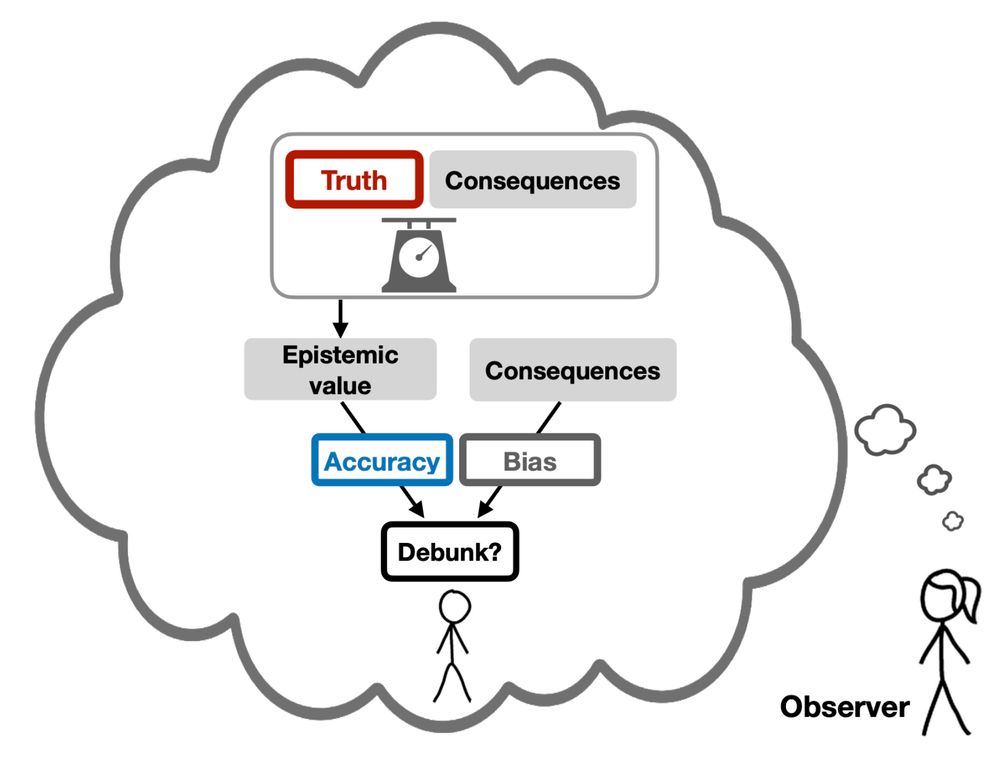

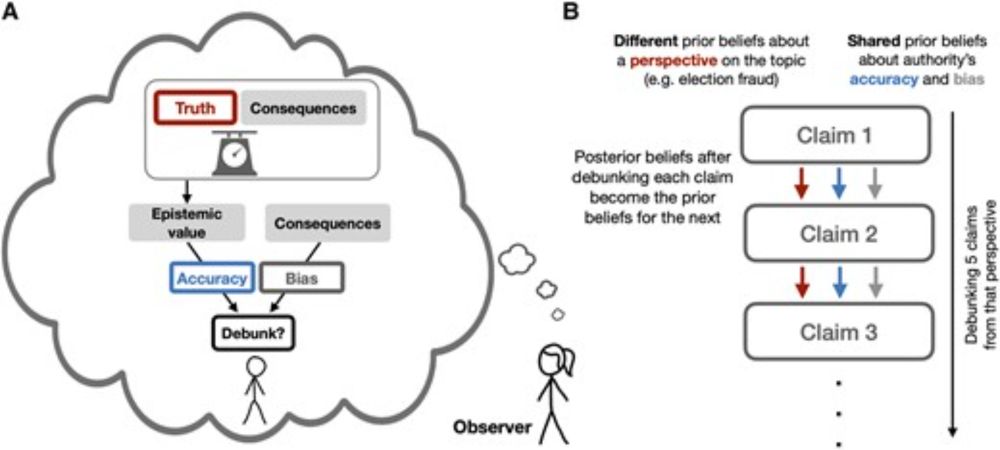

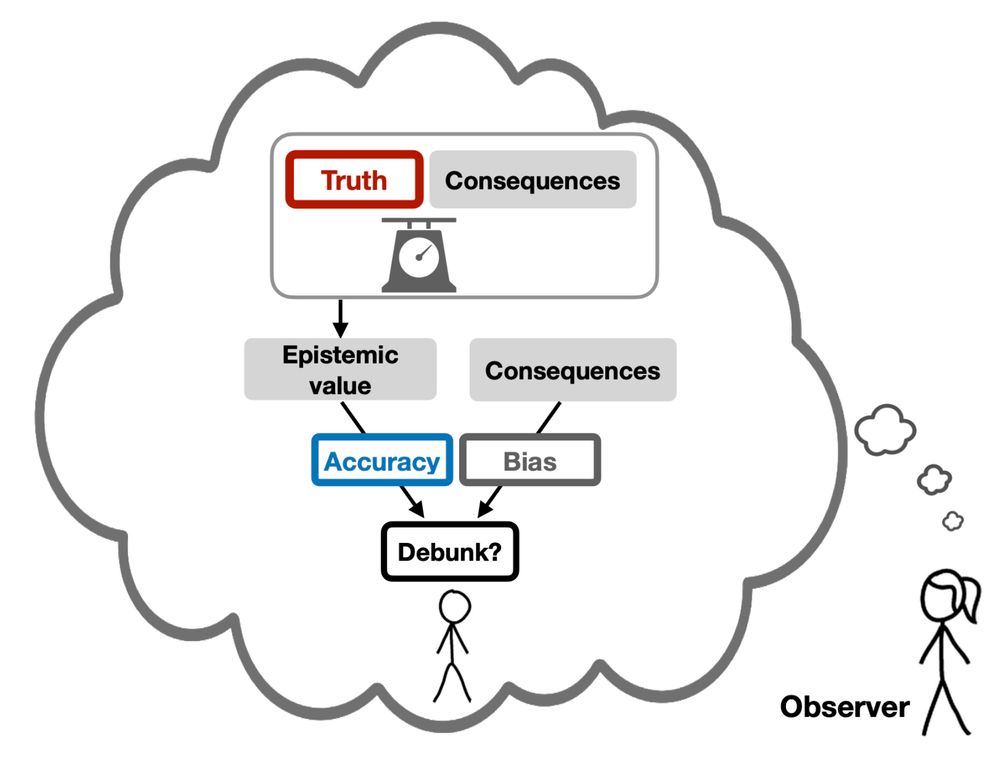

We used an inverse planning framework: people assume authorities plan punishment to achieve their desires based on their beliefs. By inverting this model, people infer the hidden beliefs and desires that most likely produced the observed punishment.

4/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 3 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

We solved this puzzle by building a computational model that characterizes “how” people interpret punishment.

Key insight: People use their pre-existing beliefs and opinions to simultaneously evaluate both the norm to be learned and the authority who’s punishing.

But how?!

3/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 3 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

This is a puzzle in life and in punishment literature!

Even when nobody disagrees about the facts—everybody knows what action happened, who punished it, and what they did to punish it—different observers of the same punishment could come to drastically different conclusions.

2/N

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 3 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

PNAS

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a peer reviewed journal of the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) - an authoritative source of high-impact, original research that broadly spans...

🚨Out in PNAS🚨

with @joshtenenbaum.bsky.social & @rebeccasaxe.bsky.social

Punishment, even when intended to teach norms and change minds for the good, may backfire.

Our computational cognitive model explains why!

Paper: tinyurl.com/yc7fs4x7

News: tinyurl.com/3h3446wu

🧵

08.08.2025 14:04 — 👍 65 🔁 28 💬 3 📌 1

1. This Friday I hosted a workshop on morality with some fabulous humans who took take time out of their lives to talk about ideas with each other. Here is a thread with brief summaries of what folks presented in case you too would like to hear about their science:

#PsychSciSky #SocialPsyc #DevPsyc

06.04.2025 21:04 — 👍 30 🔁 5 💬 3 📌 1

Saxelab Social Cognitive Neuroscience Laboratory at MIT |

The Saxe Lab @ MIT is hiring! We seek one lab manager to start in summer 2025. Research in our lab focuses on social cognition (learn more on saxelab.mit.edu).

Please apply at: tinyurl.com/saxe2025 (Job ID 31993).

Review of applications starts on March 24, 2025.

Sharing appreciated. Thank you!

03.03.2025 18:32 — 👍 54 🔁 44 💬 2 📌 2

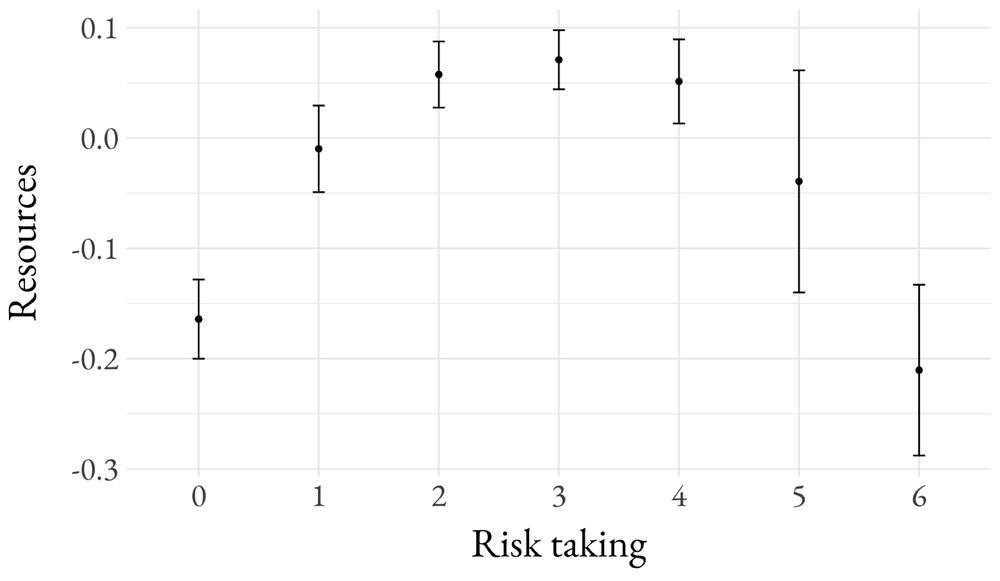

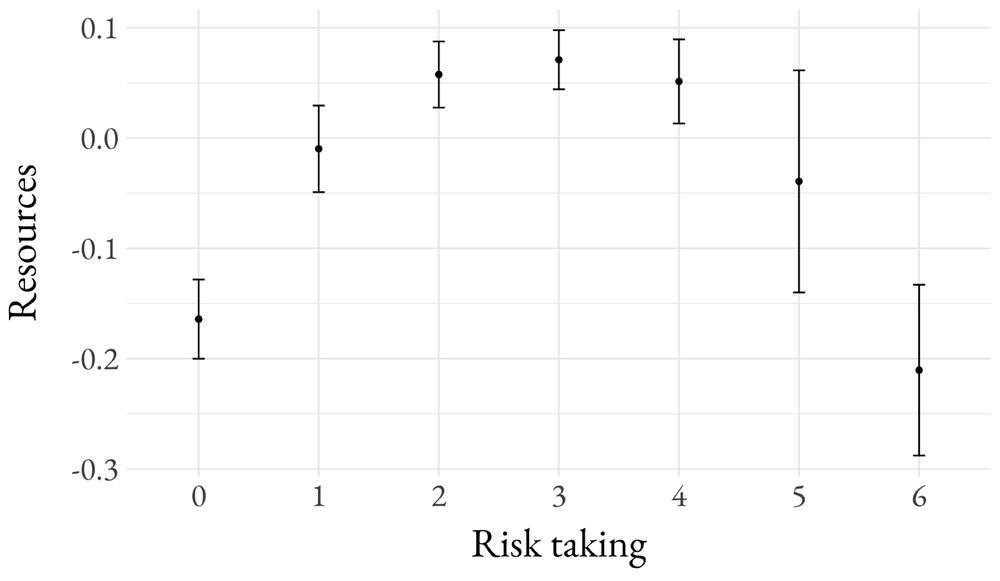

Does poverty lead to risk taking or risk avoidance? Turns out, to both. Our new paper (with D. Nettle & W. Frankenhuis) in @royalsocietypublishing.org explains why, and conducts preregistered tests of our ‘desperation threshold’ model.

royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/...

A 🧵

07.02.2025 14:12 — 👍 26 🔁 15 💬 1 📌 1

Thanks for this! Could I please be added as well?

11.11.2024 21:09 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 1 📌 0

Huge thanks to @dgrand.bsky.social , @falklab.bsky.social and @anthlittle.bsky.social for their feedback on this work, and to our funding sources!

13/13

15.10.2024 18:35 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

We need these authorities to succeed in being seen as independent and truthful, because in this space of uncertainty, those are the voices that can move people toward an accurate outcome

12/N

15.10.2024 18:33 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

Given the current 👋 state of things, this work offers insight into the challenges faced by independent election observers, public health professionals, and others seeking to cultivate credibility as debunkers

11/N

15.10.2024 18:32 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

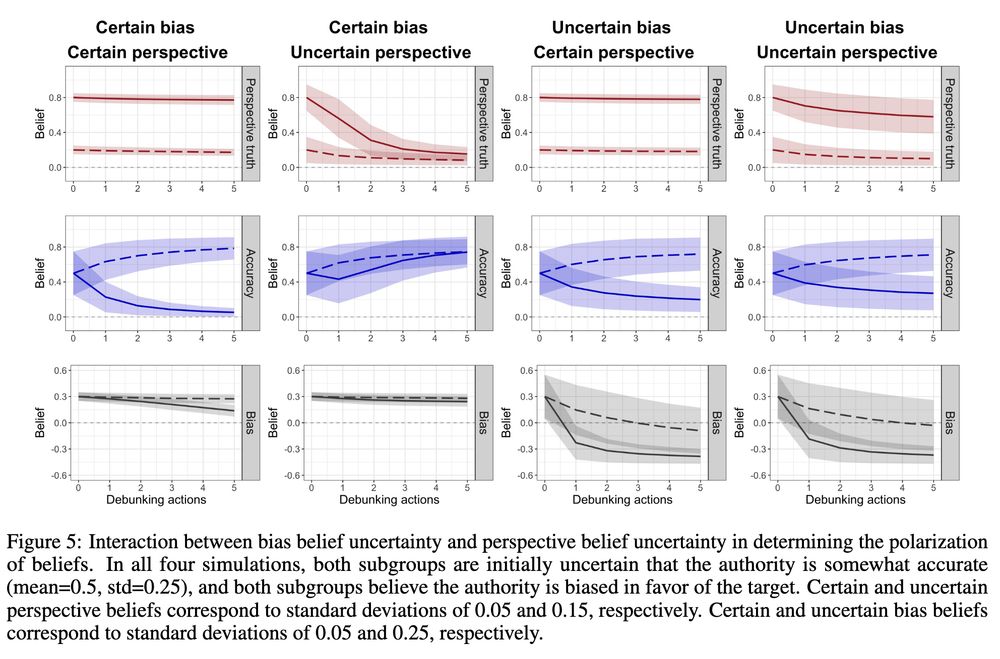

Finding 3: Differing beliefs about authorities can spread polarization

When beliefs about the authority diverge in the original domain (election fraud), their debunking can polarize the two groups in a new domain (e.g., public health) even when the groups initially share the same perspective

10/N

15.10.2024 18:30 — 👍 0 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

Finding 2: Credibility isn’t just about unbiasedness

Consistent with other work in political science, authorities seen as biased can still be effective debunkers – if they are seen as biased *in favor* of the perspective they are debunking, although this depends on the uncertainty of beliefs

9/N

15.10.2024 18:30 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

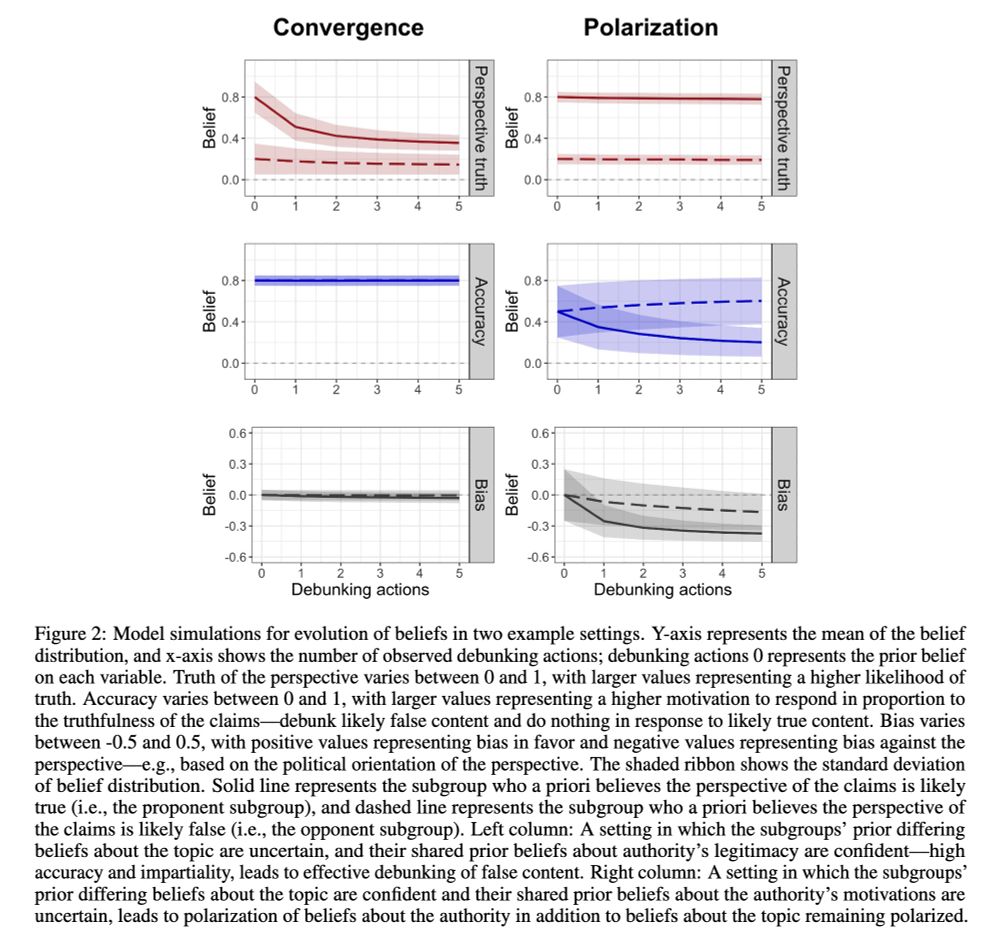

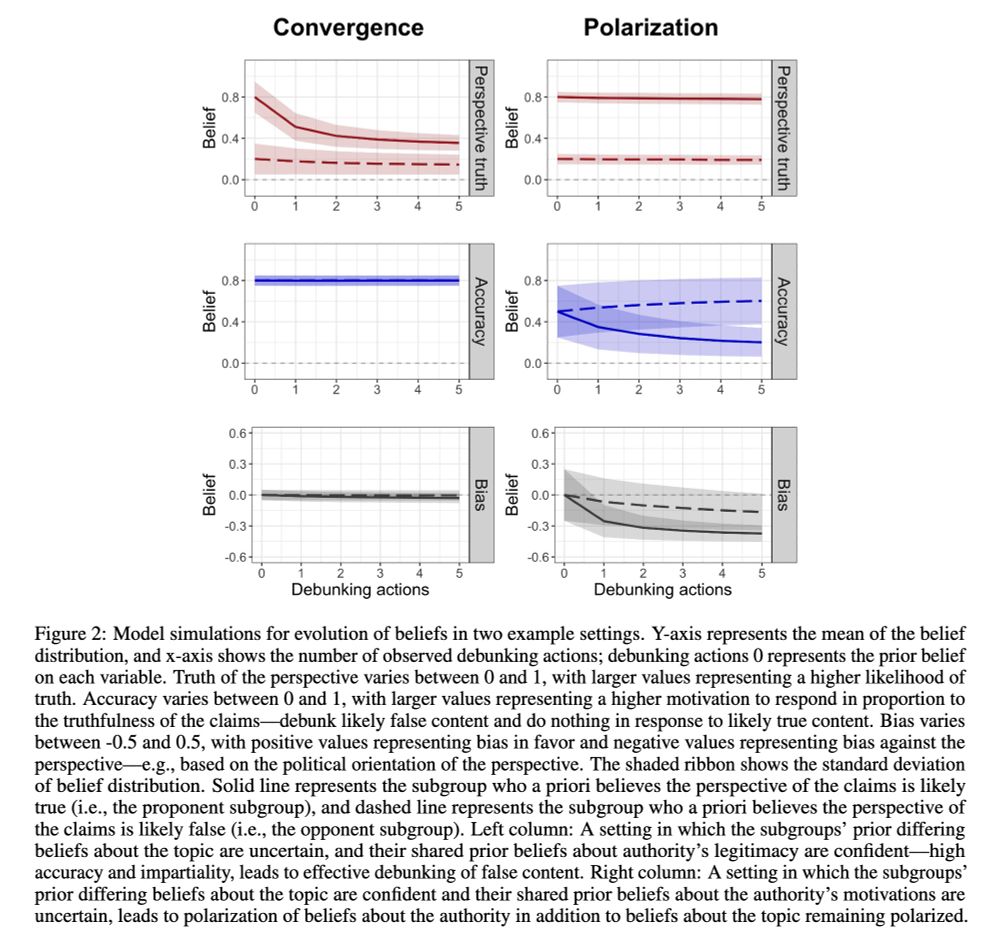

if people are certain, debunking – even by a reasonably unbiased, committed authority – fails:

1) The groups' beliefs about the perspective remain polarized

2) The groups' initially shared beliefs about the authority additionally diverge!

8/N

15.10.2024 18:29 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

Finding 1: Debunking can work…sometimes

If initial beliefs in the perspective (“the election was unfair”) are held with some uncertainty, then groups can eventually converge on shared beliefs, if they also believe the authority is unbiased and committed to the truth. But …

7/N

15.10.2024 18:27 — 👍 2 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

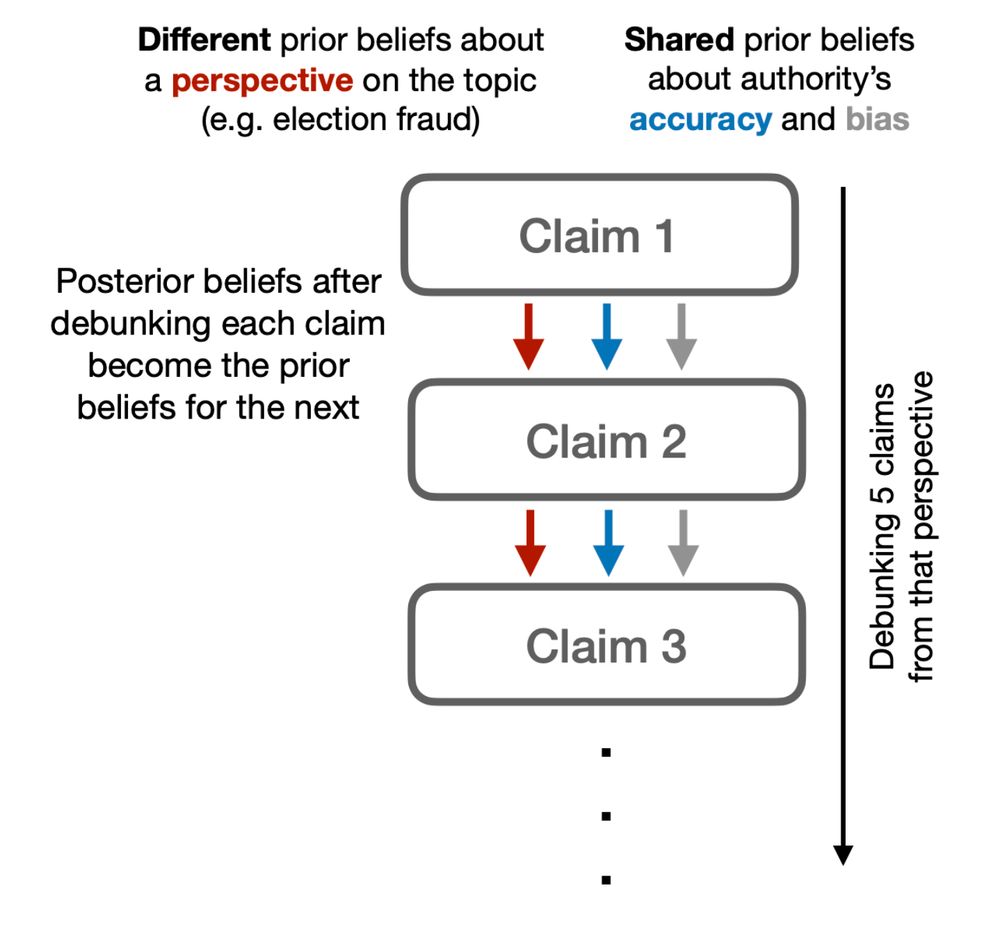

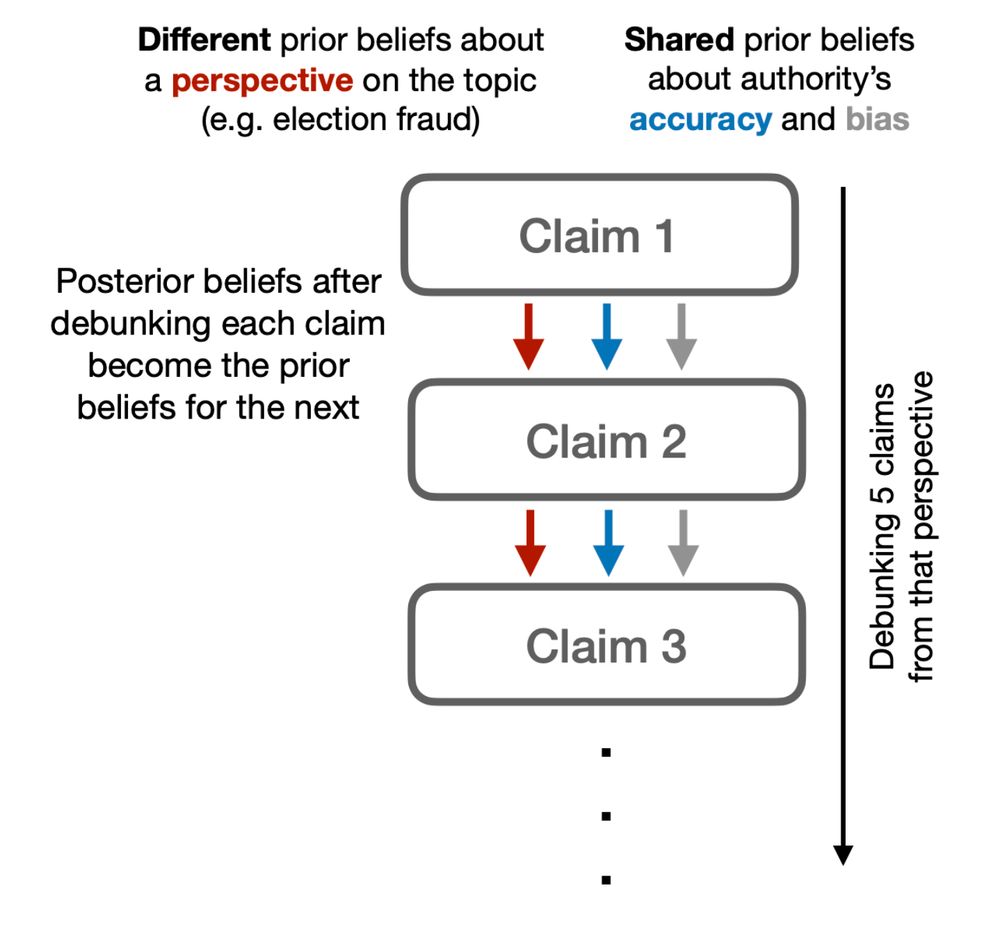

Using simulations, we capture how three related beliefs evolve: (1) commitment to the initial perspective; (2) views on the bias of the authority; (3) views on the authority’s commitment to the truth

6/N

15.10.2024 18:26 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

We use this inverse-planning framework [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19729154/] to develop a computational model of how observers’ beliefs evolve as each group witnesses 5 debunking acts that counter a single perspective on a topic (e.g., “the election was unfair”)

5/N

15.10.2024 18:25 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

We make minimal assumptions that both groups:

- Are made up of equally rational Bayesians

- Differ in their belief on a topic (ground truth may not be known)

- Hold shared beliefs about the authority’s motives with some uncertainty

(see the paper for a discussion of why these assumptions)

4/N

15.10.2024 18:24 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

We focus instead on how observers interpret debunking acts (and update their beliefs) based on their intuitive theory of the authority’s motives: degree of bias, commitment to the truth

3/N

15.10.2024 18:22 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

Lots of great work on misinformation in politics, health, etc. focuses on the content and delivery method of corrections, and on the role of biases, identities, etc. in sustaining polarized beliefs

2/N

15.10.2024 18:21 — 👍 1 🔁 0 💬 0 📌 0

Social psychologist at Ohio University studying counterfactuals, regret, free will, nostalgia, and conspiratorial thinking. Star Trek nerd. Anti-fascist. Trying to do something kind every day.

Social Justice Bard. They/them. Gay; tired.

"Maybe when it happens, you'll sink deeply into your chair

and sigh loose a breath you didn't know you were holding.

It is a pronoun. It is an event. It is a place and a time and a

certainty."

Cultural evolution - Cognitive Science - Cognitive Anthropology. Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior at Stanford GSB. Formerly postdoc fellow at the Santa Fe Institute.

Science writer and author of books including Bright Earth, The Music Instinct, Beyond Weird, How Life Works.

economist. Posts Reflect Me Only! collects/analyzes: poll, market, social media/online data, to study: news, public opinion, ads, market design

History and Philosophy of Science, Cognitive Science,Experimental Philosophy, distinguished Prof at Pitt, Director of the Center for Philosophy of Science

Climate change social scientist. Collaborator, determined dreamer, dad. Director, @ClimateSSN.bsky.social And @climatedevlab.bsky.social

www.climatedevlab.brown.edu CSSN.org personal account; reskeets NE endorsement

Brain explorer: I study the brain and write short assays, see my website: https://breininactie.com/the-brain-in-action/.

R. Feynman: I’m an explorer? I get curious about everything, and I want to investigate all kinds of stuff.

Mexican Historian & Philosopher of Biology • Postdoctoral Fellow at @theramseylab.bsky.social (@clpskuleuven.bsky.social) • Book Reviews Editor for @jgps.bsky.social • #PhilSci #HistSci #philsky • Escribo y edito • https://www.alejandrofabregastejeda.com

assoc prof, uc irvine cogsci & LPS: perception+metacognition+subjective experience, fMRI+models+AI

meta-science, global education, phil sci

prez+co-founder, neuromatch.io

fellow, CIFAR brain mind & consciousness

meganakpeters.org

she/her 💖💜💙 views mine

Luiz Pessoa, University of Maryland, College Park

Neuroscientist interested in cognitive-emotional brain

Author of The Entangled Brain, MIT Press, 2022

Author of The Cogitive-Emotional Brain, MIT Press, 2013

Neuroscience & Philosophy Salon (YouTube)

Postdoc in the Hayden lab at Baylor College of Medicine studying neural computations of natural language & communication in humans. Sister to someone with autism. she/her. melissafranch.com

Personality psych & causal inference @UniLeipzig. I like all things science, beer, & puns. Even better when combined! Part of http://the100.ci, http://openscience-leipzig.org

Assistant Professor of Technology, Operations, and Statistics @ NYU Stern

Interested in Computational Social Science, Digital Persuasion, and Wisdom of Crowds

Melbourne based PhD candidate interested in all things social reasoning, cognition, modelling, and philosophy of science 🤓

https://manikyaalister.github.io/

asst prof | clinical psychologist | some sort of geneticist | not a neuroscientist | mass general & harvard med | engagement ≠ endorsement

Psychology & behavior genetics. Author of THE GENETIC LOTTERY (2021) and ORIGINAL SIN (coming 2026).

Inspired by Cognitive Science and Philosophy.

https://www.juniorokoroafor.com/

Professor & Author

Auckland & UCL

Books: THE SOCIAL INSTINCT (2021) || THE THINKING ANIMAL (2027, ✍🏼)

Likes cycling.